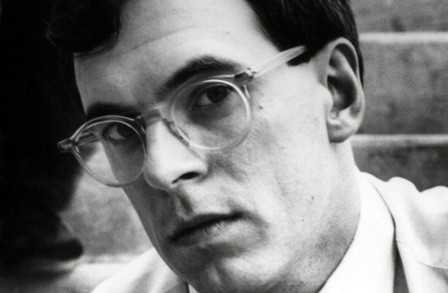

Sanky Spotlight: Tim Dlugos

Welcome to the Sanky Spotlight, where we shine a light on the talent we have at Sanky. For over 45 years, we have succeeded because of our team of trailblazing fundraisers, and to celebrate Pride Month, we’re turning the spotlight on Tim Dlugos, Sanky’s former creative director and a celebrated poet, best known for the poems he wrote during the AIDS crisis.

You may have heard of Tim Dlugos through his poetry. If you’ve read it, then you likely had the same experience as critic Marjorie Perloff, who said, “Tim Dlugos’ every nerve seems to vibrate.” Or maybe what you noticed was how simple his words seem on the surface while feeling the complexity and brilliance of his rhyme scheme in your own nerves. Possibly, you were astounded by the things you had noticed about the world but could never name — things he had the exact right words for — or by the things you had never noticed before but now can’t help but see. Christopher Wiss, Tim’s partner until his death from AIDS in 1990, says “He was alive to everything. He didn’t miss much.”

If you haven’t read Tim’s poetry or if you haven’t heard of him before reading this right now, then get ready to meet someone extraordinary. When I spoke with Christopher, he said that if there was only one thing he could share about Tim, it would be his energy and his desire to be helpful. Admittedly, that’s two things, but despite Tim’s own mastery of language, he was not someone who could be contained by the limitations of words. “He loved words. He loved playing with words. He loved puns. He and Ken Schwartz (a former Sanky staff member) used to redo the lyrics to various musicals. They would completely rework the lyrics in a very funny, amusing way. And he loved to do that. He loved crosswords.”

In his seminal poem “G-9,” written while he was hospitalized in the AIDS ward (named G-9) at Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan, Tim laments his friends who died before him and the stories lost with them. He shares some of them, but he’s left wondering, “When I pass, / Who’ll remember, who will care / about these joys and wonders?”

As it turns out, a lot of people. Since Tim’s passing, his friend David Trinidad has published New York Diary, Tim’s diary from his first six months in New York, and A Fast Life: The Collected Poems of Tim Dlugos. According to Christopher, David still submits Tim’s poems to journals and poetry collections whenever they seem like they’ll be a good fit. Outside of people who actually knew Tim, someone has composed a whole symphony based on Tim’s poems. Another person out of UC Davis is working on songs inspired by Tim’s work. And someone at Yale Divinity School, Tim’s alma mater, is working on a thesis about the church’s response to AIDS using Tim’s observations about the church, AIDS, and Catholicism in general to work through a framework of how the church can more effectively help people.

Tim was raised Catholic and was a part of the Christian Brothers from 1968-1971. “Tim was conflicted in his love of the Catholic faith he grew up in — even as the church rejected him for his ‘lifestyle’ as they insisted on calling it back then,” Judy Maneval, Sanky’s former president and Tim’s close friend, says. Religion remained an important part of his life. In 1988, a year after being diagnosed with HIV, Tim attended Yale Divinity School with the intention of becoming an Episcopal priest. “I think he got a great deal of comfort from that,” Christopher says. “He really enjoyed the path he was on that last summer, the summer of 1990, as a part of that program.”

Tim worked on Ralph Nader’s Public Citizen Newspaper in the 1970s, which led to his career in direct mail. He was a fundraising copywriter and consultant for a number of organizations including Poets and Writers, and eventually Sanky Communications (or as it was known then, Sanky Perlowin Associates), where he served as creative director. Tim worked at Sanky, either on staff or freelance, almost up until his death in 1990. Christopher remarked on the generosity Sanky showed Tim. “Harry and Judy, they paid his health insurance until the end. I mean, I don’t know what he would have done without that.”

When asked about Tim, Judy remembered, “In the late 70s and early 80s, Tim and I worked at another consulting firm. For much of that time, the office was in Westchester and Tim and I both lived in Brooklyn. Luckily, he had a car, so we commuted together.” But what has stuck with her about him aren’t the stories as much as the emotions. “Tim was a remarkable person, as all who have read his poetry will know, and a mass of contradictions. Brilliant, creative, funny, pensive, gregarious, lively, kind, often late with assignments, clever, curious about everything, talkative, irritable with editors, such great company!”

If you read both New York Diary and his poetry, you’ll recognize the names of friends, lovers, partners, and exes, who were a part of Tim’s life for decades. “He kept in touch with people. That was very important to him. When he went to Yale, he spent hours and hours on the phone. I mean, it was unbelievable,” remarks Christopher.

Tim’s social network was something else. Christopher remembers attending a party with Tim on Hudson Street where other attendees included William S. Burroughs, James Grauerholz, and Debbie Harry. But as interesting as his friends were, Christopher thinks Tim was starting to feel the pressure of the scene. “He did definitely try to pitch me on leaving New York because there was a lot of competition in the poetry scene. It wasn’t overt competition, but it was always under there.”

It was AA meetings that ended up keeping Tim in New York. “I think AA meetings helped him with AIDS and just trying to put things in perspective. I think from the poetry, you get that he was a positive person who wanted to help people, but I think he saw a lot of stuff. Some of it was, at best, inconvenient and sometimes painful.” Christopher says.

There’s a phrase queer people sometimes use to subtly denote that someone else is queer: they’re family. For so many in the community, the families they’re born into or raised by aren’t there for them after they come out, but their community is — the families they’ve found are. Being a family means fighting to make life better for you and for everyone who comes after you. It also means honoring those who came before you, who got you where you are. So this Pride Month, I’m honoring Tim.

His life, his words, and his devotion to the people he loved helped make the world a kinder, less painful place for all of us who came after him. And while there’s been a massive increase in anti-queer rhetoric in the last couple of years, we’ll fight through it for ourselves, for the queer kids who will live long after we’re gone, and for people like Tim who did the same for us. Our history is our power, is our resilience, is our now. Tim shouldn’t be our history — he should still be here — but if he has to be, then he shouldn’t get lost to time.

A small collection of Tim’s work is available for free on the Poetry Foundation website. I’ll let the poet have the last word with an excerpt from his poem, “D.O.A.”

I’d like to have a showdown too, if I

could figure out which pistol-packing

brilliantined and ruthless villain

in a hound’s-tooth overcoat took

my life. Lust, addiction, being

in the wrong place at the wrong

time? That’s not the whole

story. Absolute fidelity

to the truth of what I felt, open

to the moment, and in every case

a kind of love: all of the above

brought me to this tottering

self-conscious state—pneumonia,

emaciation, grisly cancer,

no future, heart of gold,

passionate engagement with a great

B film, a glorious summer

afternoon in which to pick up

the ripest plum tomatoes of the year

and prosciutto for the feast I’ll cook

tonight for the man I love,

phone calls from my friends

and a walk to the park, ignoring

stares, to clear my head. A day

like any, like no other. Not so bad

for the dead.

Like what you read? Check out this related post: